D. Blair: Director’s Statement

Some say the Holocaust is too monstrous to be understood, while others feel the subject is already oversaturated, two oddly mirrored and, in my opinion, erroneous positions. Certainly, the Holocaust should be studied, however imperfectly, to make sense of our modern world but, to do so, we must dig deeper and find fresh insight. The Diary of Anne Frank opened the first window on the subject in the 1950’s but it was not until the television show, The Holocaust, in 1978, that there was an updated interpretation, soon followed by the masterful documentary Shoah and Spielberg’s Schindler’s List. Since the latter is some fifteen years old, the time has come for the next level of investigation.

My research started at the Holocaust Center of Northern California, in San Francisco, and continued through university classes, extensive reading, conferences and survivor interviews (filming for myself and Spielberg’s Shoah Project). Over the course of twenty years, I have stumbled on a couple of insights that helped me get a handle on this perverse history. Why did the Germans consider Jews foreigners, even though Yiddish and Middle German are cousin languages and they lived side-by-side, with some intermarriage, since the 3rd century? It started with a legalism inherited from Gothic tribal jurisprudence: after the Goths converted, other Christians became honorary tribal members but the Jews not. Why were the Jews moneylenders? The prohibition of usury makes commerce impossible but this concept (also borrowed by Christianity from Judaism) was only enforced after Christ did not make a second millennia return. Feudal lords and clerics began to restrict Jews to ghettos and to only two professions, ragpicking and moneylending, the latter as a front for their own banking. But the discovery most critical to my understanding was that the concentration camps did not prove survival of the fittest.

I first came to Holocaust Studies, or Holocology as it can be called, at age thirty to address feelings of rage and injury derived from growing up with a secret too painful to discuss and of which I knew only the barest outlines. When I finally interviewed my mother and learned the details, although I couldn’t help but note the symbolism of my her marrying my father, a cinematographer, when I thought about film topics, I was more interested in heroics, like the story of Mordecai Anielewicz, who snuck back from Russia into the Warsaw Ghetto to lead the uprising.

I was referred to Darwin by the many references by Nazi leadership, who considered the extermination of the Jews legitimate expressions of his theory of evolution. But when I finally read him, I was surprised to find a second theory concerning sexual selection and based on relationships not power. In war time, in point of fact, helping is highlighted. For every killing there is a saving, someone keeping hope alive; hence, wars also crucially involve women and acts of kindness. In this light, I came to see my mother as innocently heroic. As men across the world went about the grisly business of murdering each other, from early 1940 to late 1944, my mother worked in hospitals, nursed the dying (often with no medicine), comforted children and snuck food to the starving. Bruno Bettelhiem, an early Holocologist, would have dismissed her, as he did Otto Frank, for irrational passivity, but was it her job to try to kill the nearest Nazi and die in the process? After the war, when there was in fact an SS man in one of her hospital beds, begging her not to give him a deadly “air injection,” she was confused: killing those she was assigned to heal was beyond her.

Conversely, flirting with a German airforce officer, who worked near her for a while assembling aircraft, restored her faith in the humanity. Although a Jewish organization we contacted for funding said they would not support positive portrayals of “fraternizing with the enemy,” we made that scene the climax of our piece. When the officer said, “What a wonderful war, every one is burnt, your mother, your father…” he was speaking in a code to avoid eavesdroppers (since fraternization was punishable by death). But he succeeded in reaching across the abyss to communicate to a Jewish woman his humanity, emphasized to the point surrealistically when he brought a gift: nylon stockings! Why didn’t the Nazi just machinegun my mother and the one thousand other young women in her transport, potential mothers of a future Jewish race? Even the Nazis sensed making young men murder young women would be psychologically unwise. Despite their limited reading of Darwin, innate sexual selection inspired the construction of assembly-line death camps, so their soldiers could operate at some remove.

Although my mother claims nothing special in her behavior, by fighting as a woman, not as a woman in the manner of a man, she added some kindness to the avalanche of atrocity and retained her humanity. So much so, my childhood, which started nine years after she emerged from the concentration camp hell, was suffused with love, romance and a trust of strangers. Certainly, if the women didn’t fight against war in this manner, success on the battlefield would mean little: returning soldiers would find women who were soul dead.

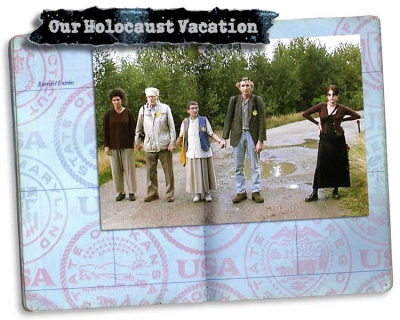

By 1997, when my brother and I realized my father was getting on in years and we had to make the trip and the movie soon, I had found a framework for interpreting my mother’s experience. Moreover, my daughter Irena was 16 and images of her with my mother would remind the viewer that the elderly woman, describing the atrocities, was a handsome teenager when they occurred. In addition to showing the female side of war, we wanted to highlight how Irena, a third generation survivor, assimilated the experience. Reaching her cohort was always central to our project, hence our inclusion of a half rock score and some funky graphics as well as our focus on her.

Making the piece autobiographical was logical, since we were a family of filmmakers on a tight budget, but it shortened the subject-object distance almost unbearably, especially for my daughter. Not only did we tell her “just be yourself” but was already in a rebellious mode, trying to maintain her identity despite the immense forces of the filmmaking, family pressures and the history buffeting her. Her foot dragging and apparent boredom annoyed us to no end and her open defiance threatened to derail the film or so we thought until we got back to the editing room and noticed she had created a great character arc, moving from recalcitrance through resistance to anguish and finally understanding.

A critical catalyst for this was in the “star scene:” when the family sewed Jewish stars and then walked through the streets of Freiberg, Germany, some wearing the stars, others not. This re-enactment, which I prefer to call a performances piece, was designed not so much to imitate but conjure an experience for better understanding, part of my effort to dig a little deeper. Although the star scene was the source of much malaise, even as my daughter Irena and sister-in-law Tania were protesting, they were testifying to its effectiveness.. A few did not produce discernable results and ended on the cutting room floor but going into Birkenau at midnight, handing out bread in Plsen (to honor Good Samaritans who fed my mother’s deportation train), as well as some other minor ones stimulated fresh insight.

Actually, Our Holocaust Vacation was originally an epic with long sections on my Polish family, additional family interactions, comments on the filmmaking process itself, and many more weird war stories — like when Tonia was kidnapped to clean house for a German woman who stomped on her fingers while she was scrubbing the floor, or when she was ordered to dump the feces bucket from a moving train and it splashed on the soldier, or when the Nazi officer walking across the camp mess hall tables, to take the head count, slipped and fell to howls of laughter (and the cancellation of two days of food). But we feel our one and a half hour version has a balanced enough view of the history and grotesqueries as well as of the women’s story and a family healing and obtaining modest understandings to provide a updated view of this critical civilization event.